Communicating Community.

I used to think of communication in one-dimensional terms: using language to represent our empirical observations to each other. The Internet has taught me some incredible things about how we communicate with each other, and what creates community. We have ideas, we need a medium of expressing…

[Old post] Pre-Snapchat thoughts I dredged up. Think it still stands.

Berkshire Hathaway invests the float

*Disclaimer* If you’re intimately familiar with Berkshire Hathaway, or with sophisticated investing in general, this isn’t an article for you.

First, a primer on insurance. Actuarial science follows the law of large numbers. As the amount of data about a certain set of activities grows, the ability to create a stochastic model that accounts for the probabilities of loss improves. The longer you hold policies for a certain type of risk, and the more similar policies you hold, the better you get at assessing the risk on those policies. And as you get better at assessing the risk, you can raise limits and lower premiums with confidence that you can withstand the inevitable losses. And so long as that activity remains popular, underwriting the risk associated with it is relevant. The government requires that an underwriter holds a certain amount the premium revenue, untouched, to pay out claims in the event of a catastrophe. Depending on the industry and type of risk, that amount of money changes. But in every case, it’s a lot. That money that sits there by law, however, doesn’t just sit under the proverbial mattress. The law allows for it to sit in certain low-risk interest-accruing positions. So, as that pool of capital sits there, waiting to pay out claims (which it rarely has to do, because of the actuarial model), it starts to earn interest. That interest is called “float”. As you might imagine, the float grows over time, because it is simply compounding interest on capital. That “float” provides capital that can then be invested. It is like having an evergreen LP, to whom you never have to return capital.

Berkshire Hathaway bought National Indemnity Company in 1967, a company that underwrites risk for personal and commercial auto, garages, construction sites, shipping, manufacturing, and distribution, etc. A few years later, they bought Government Employee Insurance Company (Yes, GEICO is owned by Warren Buffett). These companies produce billions of dollars in premium revenue, coming in every month from people like you and me, from small businesses, construction sites, garages, and real estate across the United States. This then results in hundreds of millions – and billions – of dollars *float*, which Warren Buffett and his team use to invest. So long as the infrastructure of the United States is sound, and the average consumer or small business has assets that they want to protect, Berkshire Hathaway has consistent and growing revenue streams by which to grow their business. Insurance is really good business, if you can get it.

What I love most about this is the relationship between Berkshire Hathaway, investor, and the average consumer. Indeed, a lot of the investing capital available in the United States comes from endowments and pensions, which we pay into the same way that we pay into insurance. But in wholly owning the insurers, having an evergreen capital source on his cap table Buffett seems to be closing the degrees of separation between my well-being and the effectiveness of his investment vehicles. And we are fundamentally aligned.

Using Dalio’s Economic Machine As Diagnosis

First, watch this video. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater, the world’s biggest global macro hedge fund, breaks down the economic machine into cycles of credit, debt, and growth. If it’s TL;DR, the money section (for my purposes) starts around 24:30:

Having already lowered its interest rates to zero, [the Fed] is forced to print money. Inevitably, the central bank prints money out of thin air, and uses it to buy financial assets and government bonds… It happened in 2008 when the federal reserve printed over $2 trillion in reserves… However, this only helps those who own financial assets. The central bank can print money, but it can only buy financial assets. The central government can buy goods and services, but can’t print money. In order to stimulate the economy, the two must cooperate.

In response to the deleveraging of 2008, where debt obligations were forfeited and credit dried up (at the individual and institutional level), the United States had to respond with two levels of stimulus, as Dalio points out. We know about the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which was the “big stimulus that no Republicans voted for”. That was $787 billion at the time of passage, $831 billion all told. This went towards infrastructure, education, alternative energy and unemployment benefits. We also know about Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), which was $418 billion, of which $405 billion was repaid. This went towards rescuing financial assets. What most people *don’t* know, however, is that the Fed also printed $2 trillion in loans to financial assets. On December 5, 2008 alone, the Fed provided $1.2 trillion in relief to holders of financial assets.

You may remember the political tenor of the conversation around the TARP bailout in 2008, and of the Obama stimulus in 2009. In both cases, the mainstream media would have led you to believe that it was a reasonable debate whether or not to have a stimulus, and whether or not the ones that were passed were too big. As Mr. Dalio pointed out, if a Fed stimulus for financial assets isn’t balanced with a central government stimulus for goods and services, you’ve got problems. And the Fed has, to date, spent way more money on bailing out financial assets than the central government did on goods and services. Way more. If you want to understand why we had an unequal recovery, and are facing the income inequality crisis we currently face, this is a good place to start. More on this topic soon.

Consider the un-Lean Startup

I’m very unsure about the following, but it was nagging at me yesterday, so figured I’d put it to paper. The philosophy of highly iterative, capital efficient, prototype-focused product development was popularized by by Eric Ries in his concept of “Lean Startup”. The goals of this approach to product development (and business creation) aim to get the furthest with the little capital possible, to avoid splashy launches upon which the success or failure of a company or product is determined, and to stay closer to the users; to be more human-centered.

This approach to startup development was common in web startups before Eric Ries popularized its terminology, but today it is considered gospel. I am an acolyte of lean startup methodology, and (reluctantly, haltingly) consider myself a ‘designer’, or at least a design-thinker. But, as with any opinion or perspective that becomes so wildly popular as to appear to be fact, the gospel of lean has gone a bit too far, and there are some places where entrepreneurs have challenged me to think about it differently.

Prototype:

– Try prototyping a pre-school, or a new insurance method. Not much room for error with kids and car accidents. And as startup ideas that use software/hardware get more ambitious and oriented towards important problems, more products will be much harder to prototype, like these.

Minimum Viable Product:

– MVP native mobile applications have no users. And tablet even fewer. Earning downloads on mobile is an emergent practice, and one that does not work the same way as the web. (But it works.) If you get a bunch of one- and two-star ratings early, getting back to a rating that will drive downloads is extremely difficult. Speaking of mobile…

Continuous Deployment:

– Apple takes 2 weeks to approve anything in the App Store. Continuous deployment is plain impossible with an iPhone app.

Iteration and iterate and iterate:

– Customers aren’t interested in funding R&D, but paying for products that delight; iteration isn’t an intrinsic good, but a tool. Overuse it at your peril, and end up facing the…

Pivot:

– So many startups pivot out of pressure to hack breakout growth before they run out of money. Product-market fit sometimes (often) takes a long time. And particularly when trying to make a new market, disruption means that not a lot of people will use your product or understand why it’s valuable to start. And it takes a combination of luck and perseverance to convince them.

Some of the brightest founders I’ve met recently have eschewed the lean startup model. But, interestingly, they’ve done so in opposite ways.

A few have bootstrapped – focusing early on revenue, the way a small business does, believing that they don’t have to rush to win. Paul Graham suggests that startups are companies that are designed to grow fast. Maybe I’m wrong to call these startups, then. And if these don’t eventually grow, they won’t make their investors back money. But I like them, and would actually want to invest in some of them, as a seed investor.

Others have raised (or are looking to raise) a lot more money than is typical for their stage, have built world class teams and are building with conviction, patience, and are doing actual R&D, a concept that has fallen out of favor of late. Failing to execute on Web 1.0-style ‘fat startups’ has its risks. Color famously crashed and burned, after all. And R&D processes that aren’t open run the risk of failing in the blind spots, which all teams have. But I can’t help but find these interesting too, if just because they’re unusual.

I still think the lean startup, and design-thinking (it’s fairy godmother) are highly effective ways of building a business, and of creating a product. There are more cases than not where having a beginner’s mind, building as many “listeners” into your product as possible, and optimizing for learning what your users want before spending money will lead to winning strategy. And, as with any framework, through the right lens, it can be applied anywhere, to anything. But that doesn’t make it gospel.

Contrarian Thinking: Mobile vs. PC in Emerging Markets

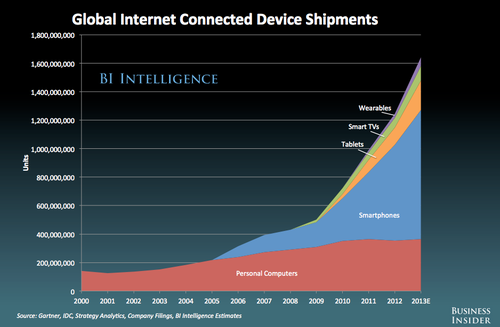

I was struck by this slide (below) of Henry Blodget’s presentation on Future of Digital. The slide is meant to demonstrate the incredible growth of smartphones and tablets, and to show that smart TVs and wearables are still young, but will soon be showing promise. But I’m more interested in the PC part of this equation. You’ll notice that the number of PC shipments per year has stayed relatively flat, and that smartphones and tablets account for the majority of Apple’s revenue, so the PC must be dead, et cetera, et cetera. The Wall Street Journal reported breathlessly that PC sales were in a tailspin last year, pointing to the 8% dip in PC sales growth. But look again: the number of PC shipments per year has stayed relatively flat, seeing modest growth.

The conclusion there seems to be: people are still buying PCs, but people who are buying their first connected device are starting with a smartphone (or tablet). And with global internet penetration still very low, of course smartphones and tablets are seeing runaway growth. But the fact that PC shipments are remaining steady suggests something to me: the PC isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

Think about it. You certainly use your computer to access the internet less now than you did before 2007, or 2010. But you still use it for MS Excel/Google Docs, for email, for photo editing and graphic design, for bug fixing and programming: for “work”. And what percentage of your colleagues and family members don’t have a computer, or rarely use one? I bet that number’s very, very low. The reason people in emerging markets are starting with a smartphone and a tablet as their first device isn’t because the PC is dead. It’s simply because they can’t afford one. But as soon as they are doing a certain amount of knowledge work, they will spend time on one. It’s way, way too early to write off the personal computer.

There have been promising innovations in netbooks, which are getting cheaper, though still (wrongly) trashing functionality in the process. The mobile arms race is bringing costs of sensors and processors way down in mobile, but in PCs. I’m willing to bet that this will bring forth a surprising surge in PC growth, once manufacturers get their costs down far enough. And until global office culture changes radically or improved gesture-controlled interfaces become ubiquitous, I think that PC is here to stay.

* There are some fascinating stealth projects currently working on this problem.

** I’m probably wrong here, so please feel free to tell me I am!

Hiring is Overrated and Underrated

The ways that it is overrated:

– Looking for ‘rockstars’ and ‘unicorns’ for commodity tasks – tasks where the skill set is fungible and common in the market. Just hire someone.

– Trying to find the A+ engineer, who will build at breakneck speed with perfectly elegant clean code, and make your entire engineering team operate better.

– MBA’s (often) get the job done. Don’t listen to the Silicon Valley mentality hating against them. One thought on that point, though: MBA’s will negotiate hard. If you’re trying to spend slowly, there are other types of business hustlers who will take underdog salaries.

The ways that it is underrated:

– Filing monopoly roles – the type of role where the set of tasks necessary for that role aren’t all that matters, but it needs to be someone who utterly shines, as well. Someone who is co-founder level good. Not every role is like that, but knowing which ones are is critical to the early days of your business.

– Even if you have a great network, the vast majority of the people worth recruiting are already doing something they love.

– When you realize you want to hire for a role, the work probably needed to get done yesterday, and it will take you a month, no matter what role you’re filing.

– Finding a good third-party recruiter, whether hiring for a venture analyst or a front-end developer, is hard. They need to understand your culture, but more importantly – most recruiters play the numbers game and really suck.

– Great engineering managers are not necessarily good developers. And vice versa.

Conclusion:

Start early, always be thinking about hiring when meeting new people, and determine what is monopoly employee versus a commodity employee. Peter Thiel introduces an interesting concept in his Stanford class from a few years back. On his view, “Some of your people will have very unique skills. Others will be more commodity employees with fungible skills.” This I enthusiastically agree with. But I’ll add that some types of work require more care, diligence, and unicorns for some companies than others. For an enterprise software startup trying to sell into schools and hospitals, a ‘monopoly’ role would be that of the salesperson, because that’s a particularly notorious challenge there, while a consumer audience startup trying to sell advertising might do fine with considering the sales job as a ‘commodity’ role.

Not many startups are thoughtful about this in the early stages, and some incorrectly assume that every employee needs to be a unicorn, while others also incorrectly believe that none need to be, so long as the culture is right. Think about the type of company you’re building, and start recruiting right now!

If FICO and Klout had a baby

Originally posted on Progress Report.

Credit, though we take it for granted, is a revolutionary human invention. Because I trust you, I will take as trade-value for this item, a payment at some point in the future. Today, though, you only get a promise. It is as old as commerce itself, and it is the grease upon which the wheels of our economic engine have run forever.

When Bill Fair and Earl Isaac created Fair, Isaac and Company (FICO) in 1956, they launched a product which had an extraordinary effect on commerce. Equifax was an O.G. big data company that had collected information on millions of Americans and Canadians. This data was used to assess risks for insurance providers, who were giving policies to consumers. FICO took data sources like Equifax to create a rating system not for insurance risk, but for any type of transaction, normalized across a set of behaviors: the credit score. Atop the credit score, companies likeVISA, Diner’s Club, and others began launching credit cards, merchants around the country and world began accepting these credit cards, and consumer credit transformed. Originally, an individual’s credit-worthiness was limited to a local store owner’s comfort-level with that individual “keeping a tab open”. It was highly localized, and based on very relatable trust and reputation.

The credit score is outdated. Companies have launched since FICO, and the bureaus themselves have their own scores. But in the Information Era, where access to data about individuals is orders of magnitude better than at any time in human history, surely the big data that informs the credit score should evolve as well.

To date, measuring credit is limited to an individual’s credit history, which is Liabilities. It is repayment history, repayment percentages, and length of credit lines. But think about the store-owner who allowed customers to “keep a tab open” and you quickly realize that there are other things to measure, which are no less powerful indicators of an individual’s likelihood to keep the promise to pay, which I’ll list below.

Assets: Someone with $1,000,000 in savings today cannot buy a car using credit if she does not have a credit card. And even if she has a credit card, if she has limited credit, because she just got the card, she will pay a big penalty, with a high-interest rate. Measuring what an individual has solves that.

Behavior: Someone who has saved 30% of his paycheck for the last 10 years, but never opened a credit card, has no credit history. If that paycheck was only $50/month, that is clearly a very trustworthy individual. And there are other indicators that are also highly relevant, if less obvious. Say, for example, that he additionally never missed a class in college, has a 401K, and spends roughly the same amount every month?

Reputation: On the social web, there are signals about who an individual is that are understood by the collection of her network. Do her friends have stable behaviors? Are there people with data trails who can vouch for her? That local store-owner would want to know that the person they are opening a tab for isn’t a stranger to the community, and so measuring that activity is, itself, an indicator.

The credit score, and credit system more generally, is broken today. A system that strictly relies on liabilities, leaves out millions of trustworthy individuals who deserve access to credit. And as our financial system increasingly moves online, and credit becomes more and more central to access to bigger purchases, this is a social issue. At Collaborative Fund, we love discovering startups whose products are radically inclusive; it’s my favorite goal of technology. And one of the most effective ways to achieve that is through credit. We will announce some investments in this category soon, so stay tuned.

Parting thought: did you know that a big part of the popularity of payday lending isn’t the immediate cash, but the fact that the lenders develop warm, personal relationships with their customers in a local vernacular? It’s a more inclusive experience than a commercial bank. Loosening up credit does not have to mean making it riskier, nor does it have to be a matter of Fed policy. Just by being empathetic, and framing the data we are already capturing, we can provide risk-adjusted credit to the millions of Americans who don’t yet have it, but deserve it.

“Social Enterprise” and “Social Impact” Confuse Me.

I always found it curious, and mildly offensive, when well-meaning peers in school would speak so enthusiastically about basket-weavers in Uganda, using the term ‘social enterprise’.

It felt at times condescending and paternalistic – it’s not a real business, because a “black woman in Africa” is doing it.

Sometimes it felt irresponsible – TOMS shoes may capture far more value than they create. And they may even hurt the very communities they purport to help.

But most of all, it’s confusing. “scalable impact” is what you’re measuring, right? Isn’t Wal-Mart creating vastly more economic opportunity and access to goods and services than that basket-weaver, or that whole network of basket weavers? (I don’t think Wal-Mart is a social enterprise by any definition, but using the extreme case to make the point.)

In the United States, economic inequality today is at its greatest level in the modern era, Spain has an unemployment rate hovering around 20%, and Nigeria and Venezuela have seen 300% increases in GDP per capita over the last decade. Is a feature phone-based gaming company started by a Kenyan for East Africa a social enterprise, but Lyft not? The macroeconomic shifts brought about by the unequal recovery of the USA and EU coupled with the inexorable rise of China, Africa, and Latin America suggests that the idea of classifying businesses’ social impact racially, geographically, or even structurally, is more and more complex; it is perhaps folly.

Bill Gates said, in reference to Google Loon a project whose goal would be to provide internet services, delivered by balloon, across the far-flug remote corners of the world, “When you’re dying of malaria, I suppose you’ll look up and see that balloon, and I’m not sure how it’ll help you.” It sparked a conversation on the internet about whether or not the social impact companies like Google and Twitter were manifesting through their work was indeed social impact. I think it was a healthy debate, and I’m torn on the issue, to be honest. It speaks to the confounding nature of social impact. What actually does make the world better?

I love what B Lab is doing to standardize the class of businesses that are focused on improving people’s lives, with ethos’ that are aspirational about society, because it starts to tell a story about enterprise, without infantilizing, being self-satisfied, and defining terms in a way that is rigorous (no one would argue that Patagonia, Etsy, or Warby Parker aren’t real businesses).

The question I hope I’m leaving you with: what type of business makes the world better? Why? At Collaborative Fund, we wrestle with this all the time, and I’m sure – well, I’m hopeful – many funds and businesspeople more generally are having this debate internally, among their leadership. The piece of the pie devoted to non-profit organizations around the world is tiny. If we’re going to vibrate goodness into the world, all hands need to be on deck, business hands especially.

Forgiveness is A Perfect Manifestation of Love.

C.S. Lewis, my favorite essayist, makes a very interesting distinction between “to excuse” and “to forgive”. In his words,

“Forgiveness says, "Yes, you have done this thing, but I accept your apology; I will never hold it against you and everything between us two will be exactly as it was before.” If one was not really to blame then there is nothing to forgive. In that sense forgiveness and excusing are almost opposites.

To excuse is to accept a reason for a wrongdoing; to justify it; to somehow lessen the blame. In this sense, we often mistake forgiving someone for actually excusing them. The way we’re able to move forward is rationalizing their action away. With forgiveness, however, we can’t rationalize away another’s action. It is inexcusable. The blame is justified, and the blame is real.

What’s fascinating to me about this (the essay talks about it in the context of God’s forgiveness of our sins) is that inherent in an act of forgiveness, is the blame itself. I take that to mean that I must actually be hurt by the action. It must be inexcusable. It must break my heart. And to be heartbroken, and somehow find a way to mend and continue like nothing happened, goodness. That’s love.